Conversations with Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was the greatest literary genius Germany has ever produced. His first of many masterpieces, The Sorrows of Young Werther, made him a celebrity throughout Europe at age 25. He remained a dominant figure in European society until his death in 1832, at age 82.

It is pointless to translate Goethe’s plays, poems and ballads into English, therefore most of his work remains out of western mainstream.

Johann Peter Eckermann, a young poet, had become his assistant and mentee during the last years of Goethe’s life. Luckily, he had the good sense to take notes, which were published after Goethe died as Conversations with Goethe (Gespräche mit Goethe).

I first read these conversations during my time in Barcelona where I was training as fine artist. It was the right time in my life to hear Goethe talk shop.

Almost everything Goethe says carries a profound insight that comes from a lifetime of love, loss, exploration, virtuosity and, unique to him, being a polymath and Europe’s all-time greatest poet. His words resonated deep within me and changed me and my approach to art.

I agree with Eckermann: “…I found the human heart in all its desire, happiness and suffering I found a German nature like the present bright day”

I share my notes here, because nobody I know, including Germans, read the book and I felt more people should know that it exists.

Translating Goethe is lossy, so I also published the original German excerpt.

Beware of Big Plans

All young poets in Germany should know it, it could help them. He started the conversation by asking me if I hadn’t written any poems this summer. I replied that I had made a few, but that I was lacking in comfort. “Take care,” he said, “of a great work. That is what our best suffer from, precisely those who have the most talent and the most diligent striving.

I too have suffered from it, and I know what it has damaged me. What a lot of things have fallen into the well! If I had done everything that I could have done quite well, not a hundred volumes would have been enough.

The present wants its rights; that which daily imposes itself on the poet of thoughts and feelings wants and should be expressed.But if one has a greater work in mind, nothing can come to nothing, all thoughts are rejected, and one is so long lost for the comfort of life itself.

What effort and use of spiritual power does not belong to it, just to order and round off a great whole within oneself, and what powers and what calm undisturbed situation in life, in order then to pronounce it properly in a river.

If the whole is out of order, all effort is lost; if, furthermore, in the case of such an extensive subject,the individual parts are not completely master of their substance, the whole will be deficient in places, and one will be scolded; and from all this, instead of reward and joy for so much effort and sacrifice, nothing but discomfort and paralysis of the powers arises for the poet. If, on the other hand, the poet grasps the present every day, and if he always treats what is presented to him in a fresh mood, he always does something good for himself, and if he does not succeed in something, nothing is lost.

There is August Hagen in Königsberg, a wonderful talent; have you read his ‘Olfried und Lisena’ ? There are places in it that couldn’t be better; the conditions at the Baltic Sea, and whatever else strikes a chord with the locality there, everything masterly. But they are only beautiful places, as a whole nobody wants to feel comfortable. And what effort and what forces he has put into it! Yes, he has almost exhausted himself. Now he has made a tragedy!”

On Freedom and Constraints

And what good is an abundance of freedom that we cannot use! See this room and this adjoining chamber, in which you can see my bed through the open door, both are not big, they are anyway limited by many needs, books, manuscripts and art things, but they are enough for me.

If one has only so much freedom to live healthily and to do one’s trade, one has enough, and so much is easy for everyone. And then we are all only free under certain conditions.

Goethe strove for the most versatile insight, but in his life’s work he limited himself to only one thing. He practised only one art, and practised it masterfully, and that was to write German. That the material he spoke was of a versatile nature is another matter.

“But apart from that,” said Goethe, “the greatest art is to limit and isolate oneself. “I’ve spent too much time on things,” he said one day, “that weren’t my specialty. When I think about what Lopez de Vega did, the number of my poetic works seems very small. I should have stuck more to my real profession. If I hadn’t spent so much time with stones,” he said another time, “and had used my time for something better, I could have had the most beautiful jewelry of diamonds.”

”[…] Without a lifelong preoccupation with the fine arts,” Goethe said, “it would not have been possible for me. The difficult thing, however, was to remain moderate in the face of so much abundance and to reject all such figures that did not quite fit my intention. For example, I made no use of the Minotaur, the Harpies and some other monsters.”

“But you won’t find a word about music, and that’s because it wasn’t in my circle. Everyone must know what to look for on a journey and what is his business.”

Learn the General, Express the Specific

“It’s a mistake,” I said, “that runs through all of contemporary literature. One avoids the special truth for fear it is not poetic, and so falls into commonplaces.”

“Yes” said Goethe, “and then, as long as we keep to the generalities, anyone can imitate us, but no one imitates the particular. Why? Because others have not experienced it. Nor need we fear that what is specific will not be appreciated. Every character, however peculiar it may be, and every thing to be represented, from the stone up to the man, has a commonality; for everything is repeated, and there is no thing in the world that is only once there.

On Philosophizing or Intellectualizing Your Art

An idea can drown in its description.

“Philosophical speculation is a hindrance, as it often brings into its style a non-sensual, incomprehensible, broad and unravelling being. The closer they devote themselves to certain philosophical schools, the worse they write. Those Germans, however, who as business and leisure people only go for the practical, write best. Thus Schiller’s style is most splendid and effective when he does not philosophize.”

It was not Schiller’s thing,” Goethe continued, ”to proceed with a certain unconsciousness and, instinct, but rather to reflect on everything he did; wherever it came from, he could not refrain from talking back and forth a great deal about his poetic intentions, so that he talked through all his later plays scene by scene with me. On the other hand, it was completely against my nature to talk about my poetic intentions to anyone, not even Schiller. I carried everything quietly with me, and no one usually learned anything until it was finished. When I presented my ‘Hermann and Dorothea’ to Schiller, he was surprised, because I had not told him a single syllable before that I intended to do something like that.

Schiller looked at his object only from the outside, as it were; a quiet development from the inside was not his thing. His talent was more desultory. That’s why he was never decisive and could never finish.

Ideas are Fragile: Birthed at Night in Dim Light

“That undisturbed, innocent, somnambulistic creation, whereby alone something great can flourish, is no longer possible. Our current talents are all on display to the public. The critical papers appearing daily in fifty different places and the gossip that this causes in the public does not allow anything healthy to emerge. Anyone who does not completely refrain from doing so nowadays and does not isolate himself by force is lost.

Admittedly, the bad, largely negative aestheticizing and criticizing newspapers bring a kind of semi-culture into the masses, but to the producing talent alone it is an evil fog, a falling poison that destroys the tree of his creative power, from the green ornament of the leaves to the deepest marrow and the most hidden fibre.

And then, how tame and weak life itself has not become since the ragged few hundred years! Where else can we find an original nature unveiled! And where does one have the strength to be true and show himself as he is! But this has an effect on the poet, who should find everything within himself, while from the outside everything lets him down.”

On Knowing Yourself

“It has been said and repeated at all times,” Goethe continued, “that one should strive to know oneself. This is a strange demand that no one has yet satisfied, and no one should actually satisfy it.

He knows of himself only when he enjoys or suffers, and so he is taught what he has to seek or avoid only through suffering and joy. By the way, man is a dark being, he does not know where he comes from or where he is going, he knows little about the world and least of all about himself. I do not know myself either, and God shall protect me from that as well.

On False Tendencies

The terrible thing is,” Goethe continued, “that one has been hindered in life so much by false tendencies, and that one never recognizes such a tendency until one has already made oneself free.”But what is the point,” I said, “in seeing and knowing that a tendency is a false one?”

The wrong tendency,” Goethe replied, “is not productive, and if it is, then what is produced is of no value. To become aware of this in others is not so difficult, but in oneself, is a thing of its own and wants a great freedom of the spirit. And even recognition does not always help; one hesitates and doubts and cannot make up one’s mind, just as it is difficult to break away from a beloved girl, of whose infidelity one has long had repeated proofs.

Think For Yourself. Beware of Too Much Culture

“The seductive thing for young people,” said Goethe, “is this. We live in a time when so much culture is so widespread that it has, as it were, communicated itself to the atmosphere in which a young person breathes. Poetic and philosophical thoughts live and move within him, he has absorbed them with the air of his surroundings, but he thinks they are his own, and so he pronounces them as his own.

But after he has given back to time what he has received from it, he is poor. He is like a spring that has been bubbling with added water for a while and that stops trickling as soon as the borrowed supply is exhausted”.

Truth is Rediscovered by The Individual. Error by the Masses.

“Generally,” Goethe continued, “the world is so old now, and so many important people have lived and thought for thousands of years that there is little more to be found and said. My theory of colors is not entirely new either. Plato, Leonardo da Vinci and many other great men have found it and said it in detail before me; but that I also found it, that I said it again, and that I strove to bring truth back into a confused world, that is my merit. And for the true must be repeated again and again, for error is also being preached about us again and again, not by individuals but by the masses.

In newspapers and encyclopedias, in schools and universities, everywhere error is on top, and it is comfortable for him to have the majority on his side. “Everything great and clever,” he said, “exists in the minority. There have been ministers who had the people and the king against them, and who carried out their great plans alone. There is never any thought of reason becoming popular. Passions and feelings may become popular, but reason will always be in the possession of some exquisite individual.”

Make Art Your Religion

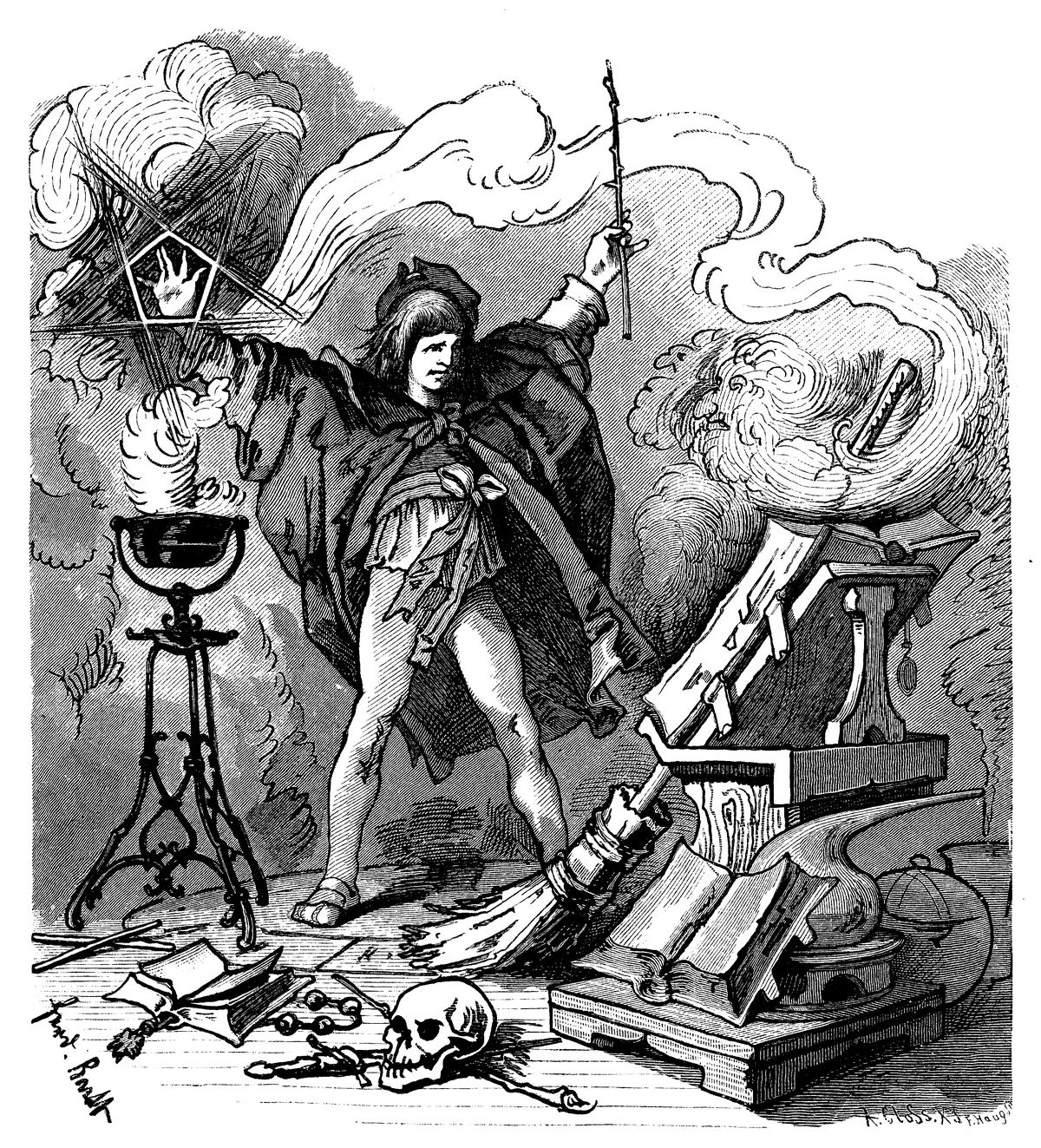

[…] the wrong tendency of such artists who want to make religion into art, whereas their art should be their religion. “Religion,” said Goethe, “stands in the same relationship to art as any other higher interest in life. It is to be regarded merely as a substance that has equal rights with all other substances of life. Nor are faith and unbelief by any means the organs with which a work of art is to be conceived; quite different human powers and abilities belong to it.

“The typical artist,” said Goethe, “always wants to be finished and has no pleasure in the work. But the real, truly great talent finds its greatest happiness in the execution.

Art as such is not enough for lesser talents; during the execution they always have in mind the profit they hope to achieve through a finished work. But with such worldly purposes and directions, nothing great can come about.”

Find a Worthy Object for Your Art

“Yes,” said Goethe, “what is more important than the objects, and what is all the art teaching without them. All talent is wasted if the object is no good. And it is precisely because the new artist lacks worthy objects that all the art of modern times is in short supply. We all suffer from this; I could not deny my modernity either.

On Getting Older and Shifting Levels of Insight

[…] experience, however, is that one experiences what one would not like to have experienced’. “Yes,” said Goethe laughing, “these are the old jokes with which we so shamefully spoiled our time!”

“One always thinks,” said Goethe laughing, “one must grow old to be clever; but basically, with increasing years one has to keep oneself as clever as one has been. Man may well become a different person in different stages of life, but he cannot say that he will become a better one, and he may be right in certain things as well as in his twentieth year as in his sixtieth.

Of course, one sees the world differently in the plains, differently on the heights of the foothills, and differently on the glaciers of the primeval mountains. One sees one part of the world more in one point of view than in another; but that is all, and one cannot say that one is more right in one point of view than in another. Therefore, if a writer leaves behind monuments from different stages of his life, it is most important that he should have an innate foundation and good will, that he should see and feel pure at every stage, and that he should have said justly and faithfully what he thought, without secondary purposes.

Then his writing, if it was right on the level where it was written, will also remain right in the distant future; the author may also develop and change later as he wishes.

Youth or age can be a good thing or a hindrance, and the artist must therefore consider his years and then choose his subjects.

I succeeded in my ‘Iphigenia’ and my ‘Tasso’ because I was young enough to be able to penetrate and revive the ideals of the material with my sensuality. Now, at my age, such ideal objects would not be suitable for me, and I am more likely to choose those where a certain sensuality is already in the fabric.

Apprenticeship Under a Living Master

[…] this way of feeling and seeing nature has completely disappeared, our painters lack poetry. And then our young talents are left to their own devices, they lack the living masters to introduce them to the secrets of art. Admittedly, there is something to be learned from the dead, but this alone is, as it turns out, more a relinquishment of individual details than an intrusion into a master’s deeper way of thinking and acting”.

[…] It is not enough that one has talent, it is more necessary to have it in order to become clever; one must also live in great circumstances and have the opportunity to see the playing figures of the time in the cards and to play along with his own profit and losses.

On Musical Talent Being Independent

“Musical talent,” said Goethe, “can show itself earliest in that music is something quite innate, something within, which does not need much nourishment from the outside and no experience drawn from life. But of course, an appearance like Mozart always remains a miracle that cannot be explained further.

What a Poem Should Do

“Ohh, so much to define!” said Goethe. “Lively feeling of the inner state and ability to express it makes the poet.”

“This poem is beautiful, they say, thinking only of the sensations, the words, the verses. But nobody thinks that the real power and effect of a poem lies in the situation, in the motives. And for this reason thousands of poems are seen as very strange to scholars who seem to think that poetry does not happen from life to poem, but from book to poem…”

Courage and Doubt

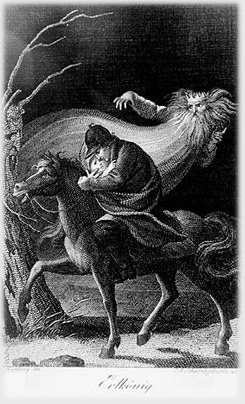

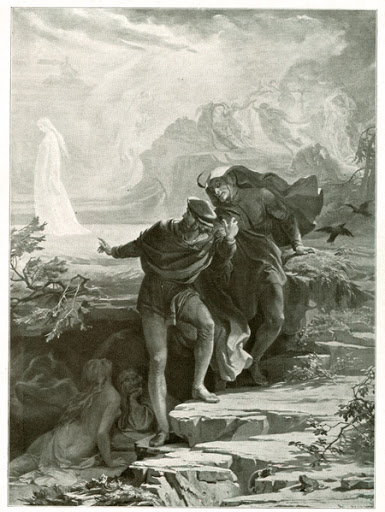

I read the New Testament and remember an image that Goethe showed me in those days, where Christ walks on the sea and Peter, coming towards him on the waves, immediately begins to sink in a moment of walking discouragement. “This is one of the most beautiful legends,” said Goethe, “that I love above all others. It is a great lesson that man will win the most difficult enterprise through faith and fresh courage, but that he will be lost at the slightest doubt.

Goethe’s Perspective on His Work

We talked about the many years he spent directing the theater and the endless time he lost for his literary work. “Of course,” said Goethe, “I could have written many a good play, but when I think about it, I am not sorry. I have always looked at all my work and achievements only symbolically, and I was basically quite indifferent whether I was making pots or bowls.